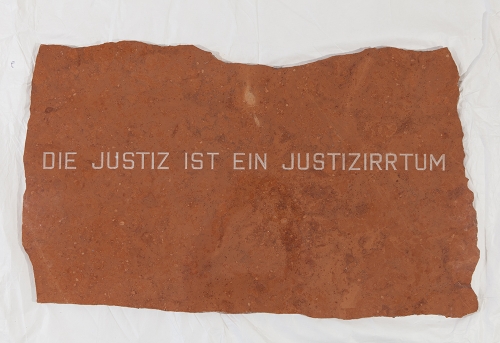

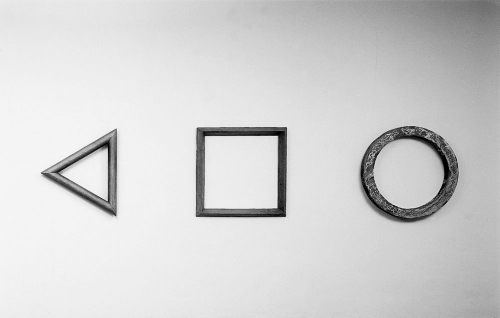

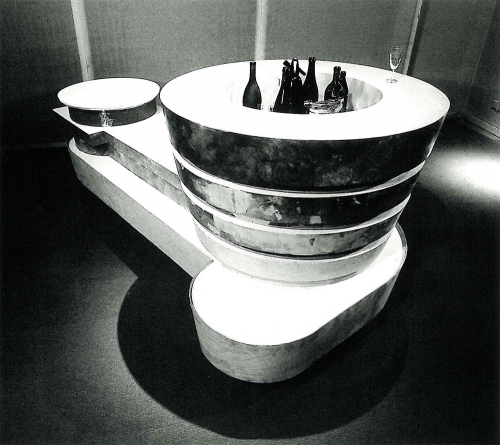

Limestone, neon

‘The spiral named after the mathematician Blaise Pascal has a mathematical singularity. The angle of the curve is calculated in such a way that the center of the spiral lies in the infinite. Pascal saw in it a model for the human soul, as in the Christian belief system the soul lives forever, that is in the infinite. Mathematics, which is so powerful in explaining our physical universe, operates both in the realm of mind and matter. To see a great philosopher and mathematician like Pascal develop a mathematical formula to solve a material but also an existential problem is very surprising and touching.’

Tap and Touch

Cinema

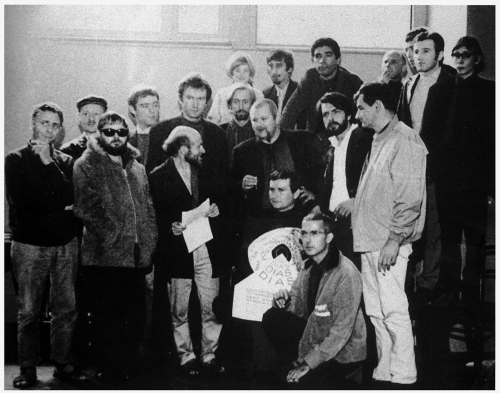

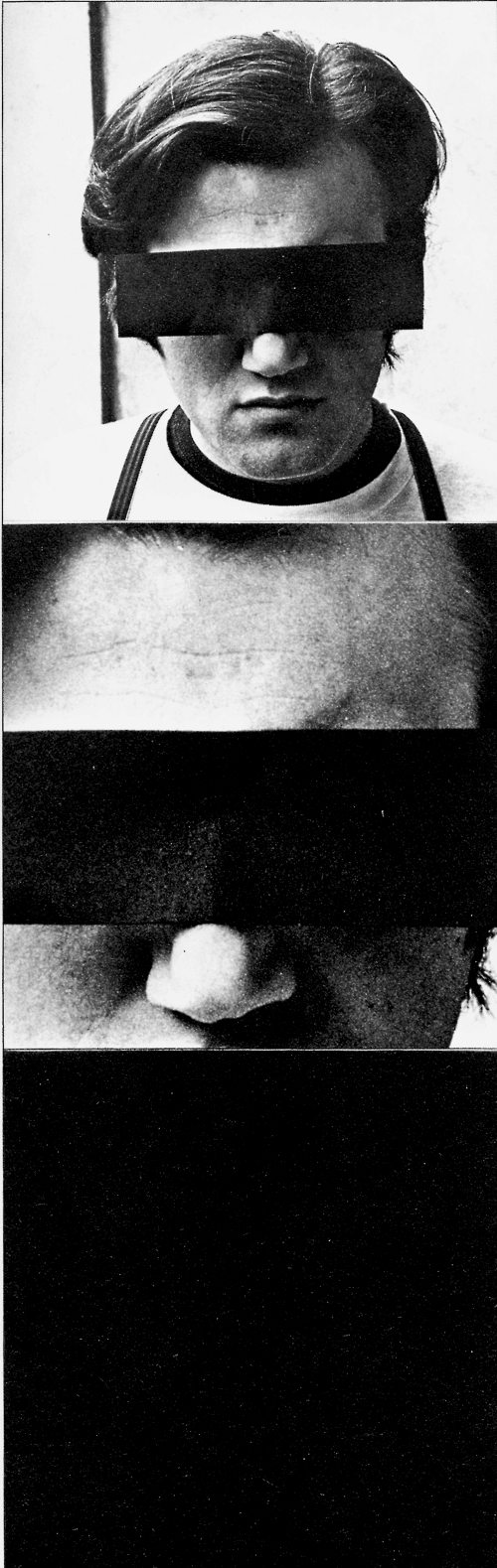

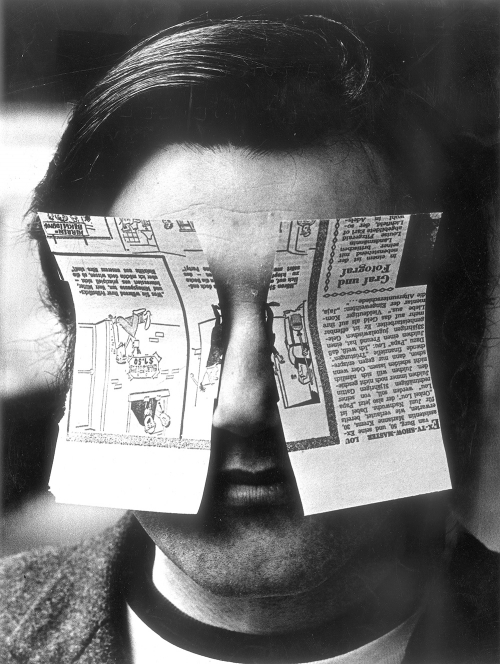

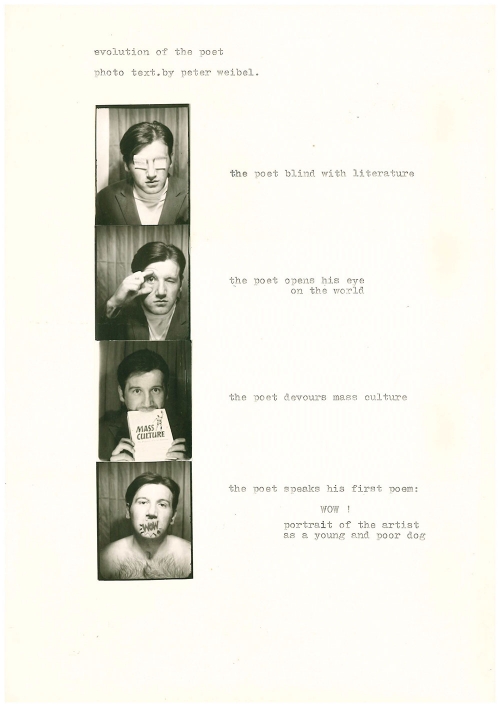

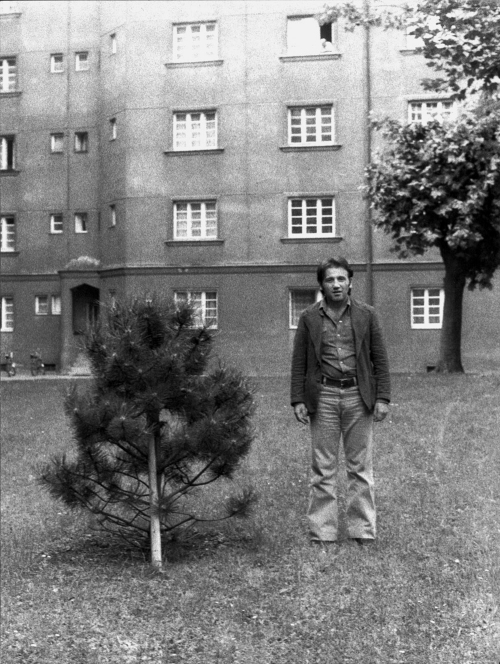

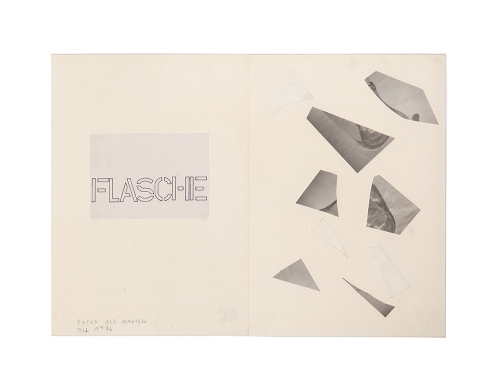

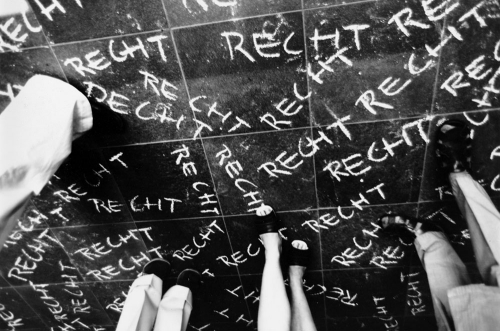

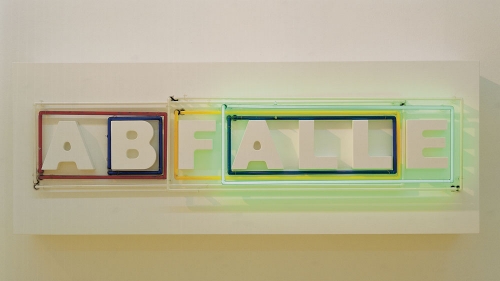

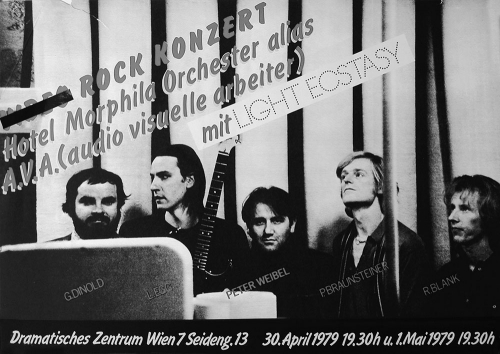

Peter Weibel’s way into art lay through visual poetry, which he understood in the broadest sense possible. Poems took the shape of radical performances, actions or objects, eventually evolving into a kind of total artistic experiment without any genre or stylistic limitations. The key element that persisted in Peter Weibel’s works was the critique of structures (language) and phenomena (bourgeois culture, media, institutions) that define our life and our thinking. It is precisely this element that allows us to envisage the very versatile body of work as a single project of exploring the possible.

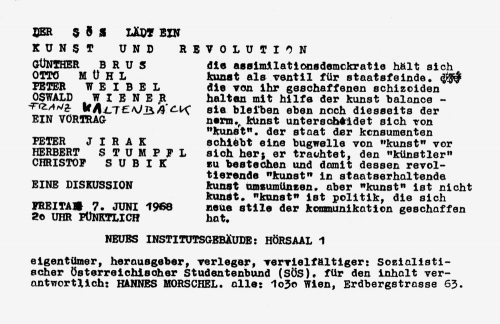

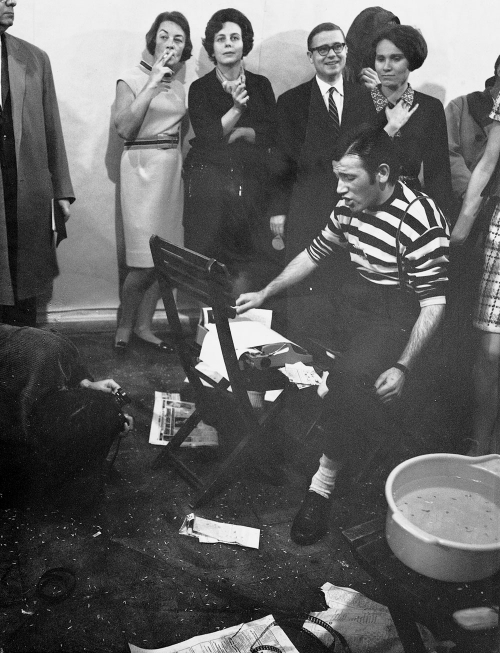

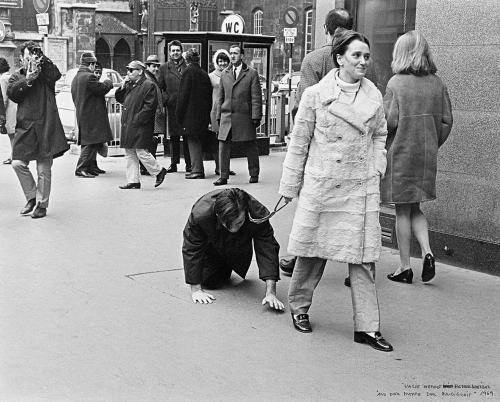

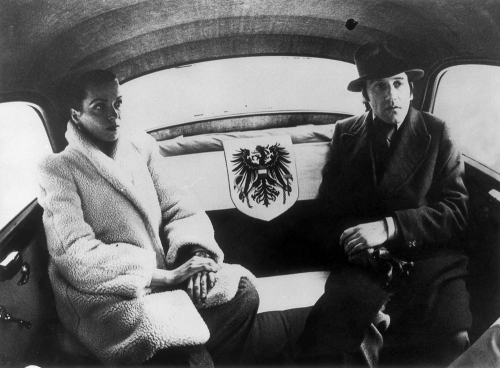

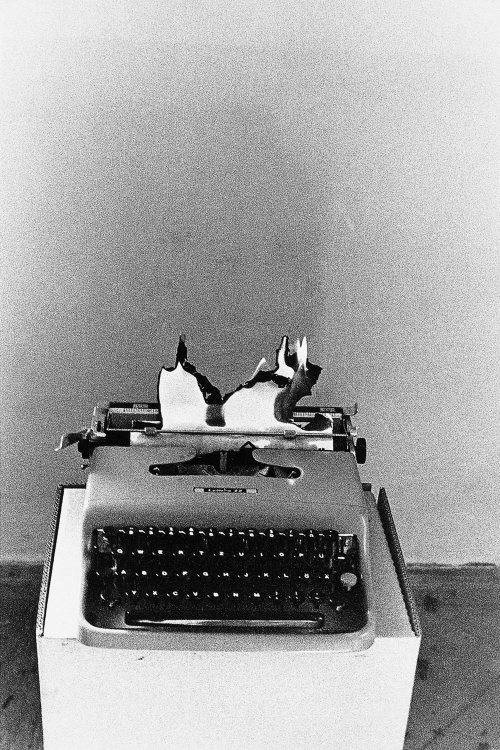

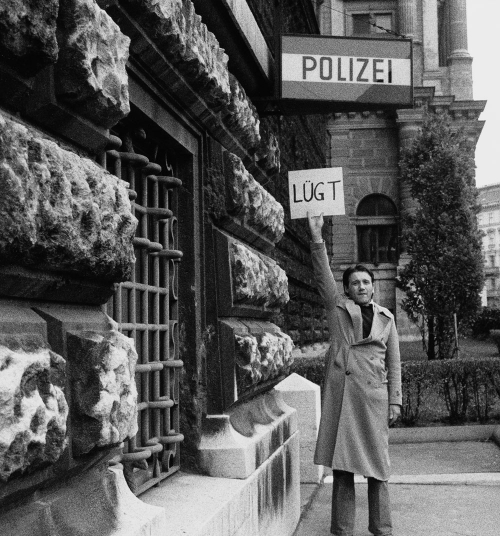

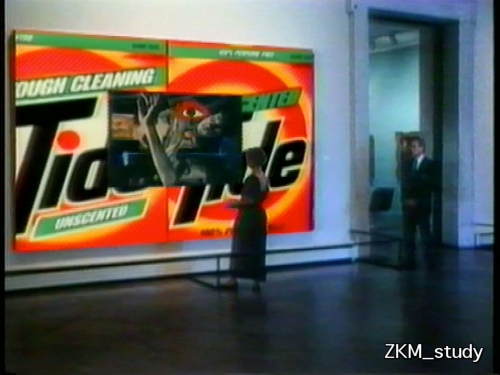

In the late 1960s, Peter Weibel with a group of radical Viennese artists provoked society by subverting its rules and routines to reveal its contradictions — testing the boundaries of what was possible in a bourgeois society and challenging its institutions.

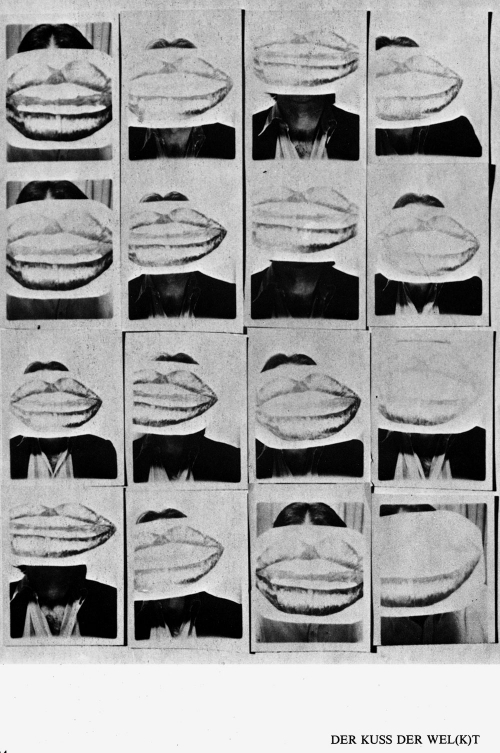

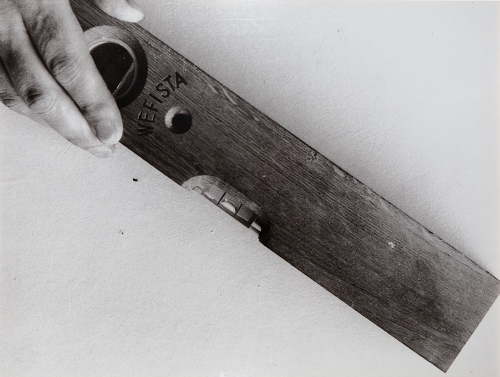

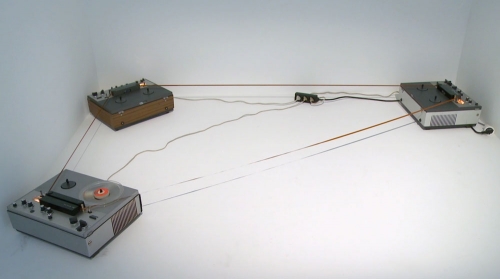

Similarly, he explored and pushed the boundaries of media. Transferring the principles of a particular medium to a different context, applying the logic of a certain technology to something completely different, he distilled the essence of media and examined its ability to change our perception of the reality.

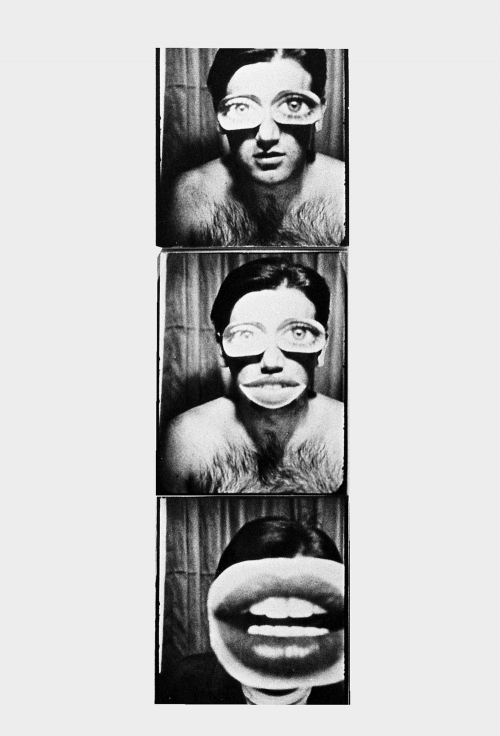

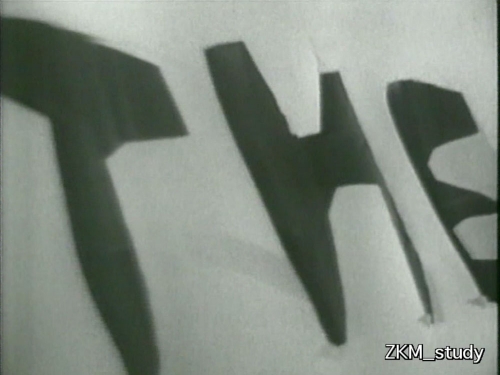

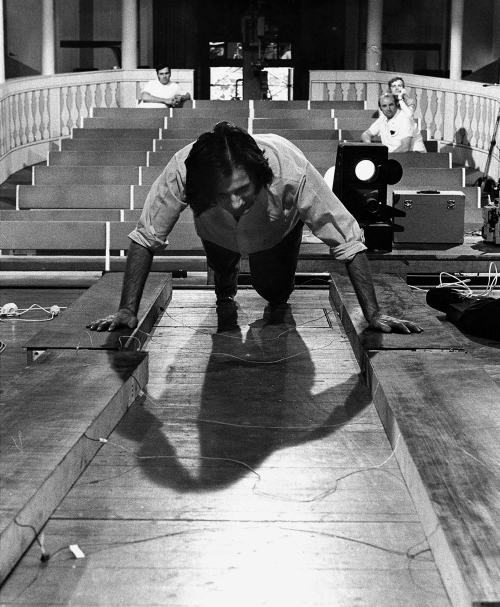

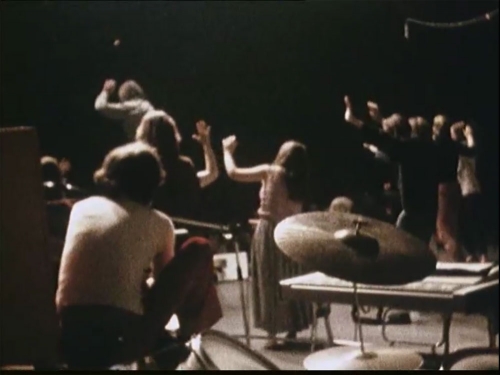

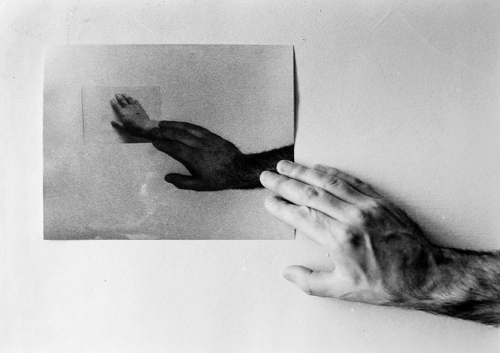

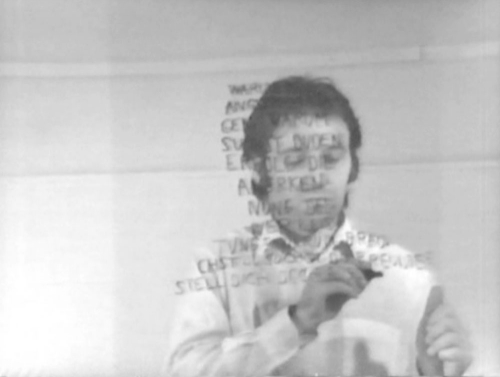

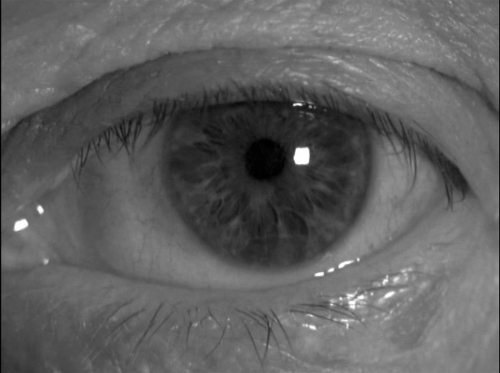

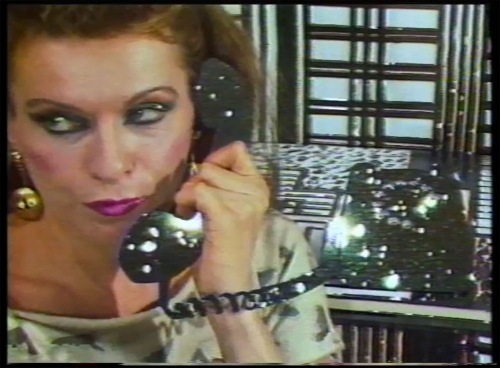

In Peter Weibel’s and Valie Export’s Tap and Touch Cinema the artist’s body replaces the screen, and the deceit of voyeurism gives place to unmediated tactile reception. In Cutting, an expanded cinema project of theirs, reality is edited as it is being shot: instead of film, it is the objects within the frame that are being cut with common scissors. In Fingerprint, both the soundtrack and the image are created by the artist touching the 35 mm film with a painted finger and recording (instead of what is normally visible and audible) the physical reality of the human body.

Tap and Touch

Cinema

Paradoxes of

Perspective

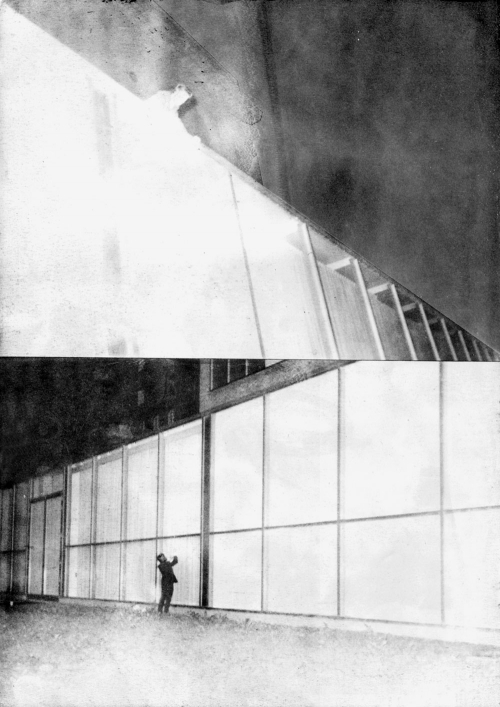

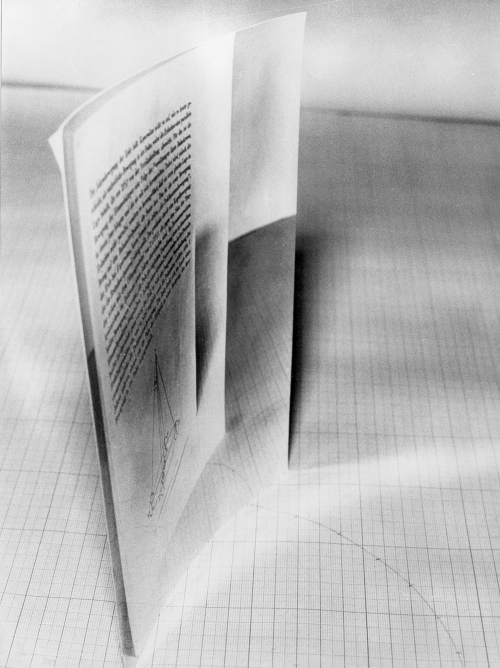

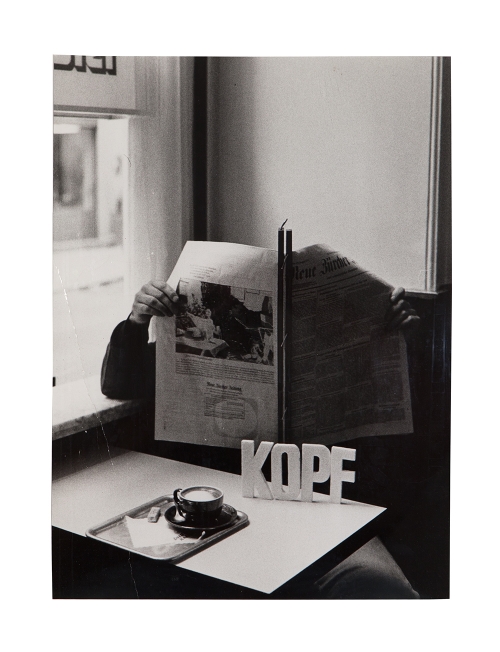

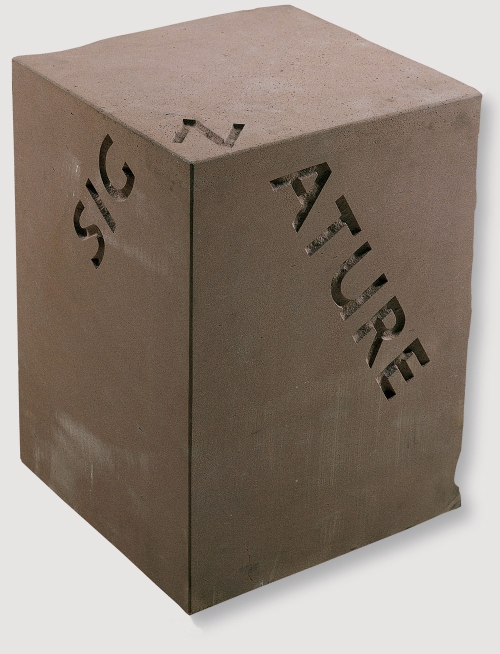

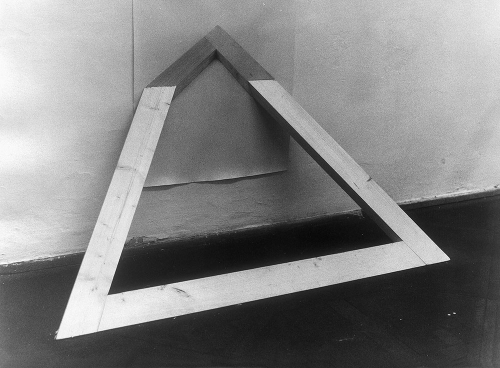

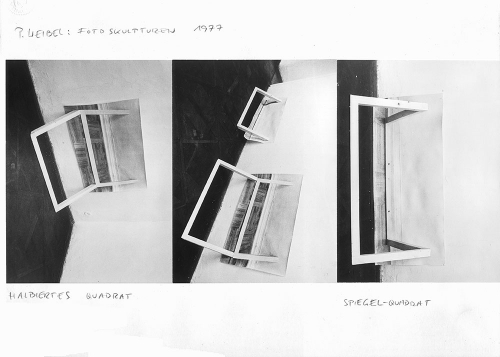

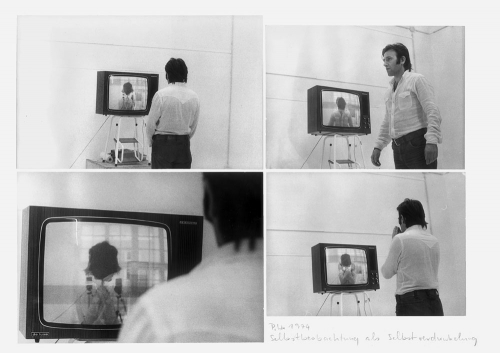

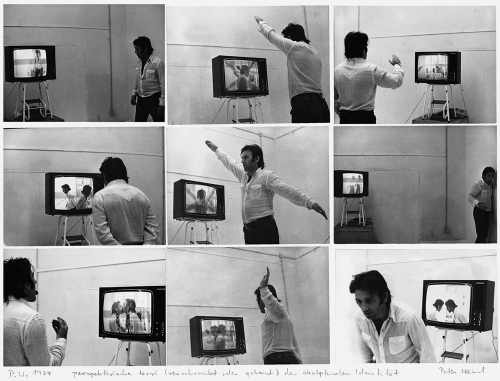

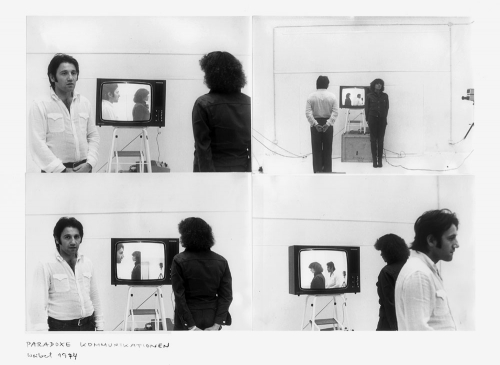

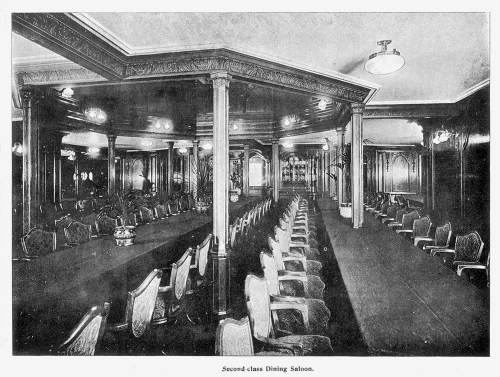

Ultimately exposed as inaccurate depiction of reality distorting our idea of what is real, photography has been haunted by a critique denouncing attempts to represent the 3-dimensional world on a flat surface from its earliest days. In art, painting was the first to turn its eyes upon itself and examine the illusions of representation, while photography and video largely followed the painterly tradition. Peter Weibel’s work, however, seems to have arisen from a different approach suggested earlier by the photographic experiments of Eadweard Muybridge: exploring photography as a specific technology, which creates a reality as different from the one we see in paintings as it is from the physical reality we inhabit. What are the physical laws that define this world? And what opportunities does it open before us in comparison to our own?

With a background in mathematics and logic, Peter Weibel explores the reality created by photography and video like a scientist would explore a newly discovered planet, revealing the physical and logical paradoxes and distortions it generates, and the tools for social or institutional critique it may offer.

Paradoxes of

Perspective

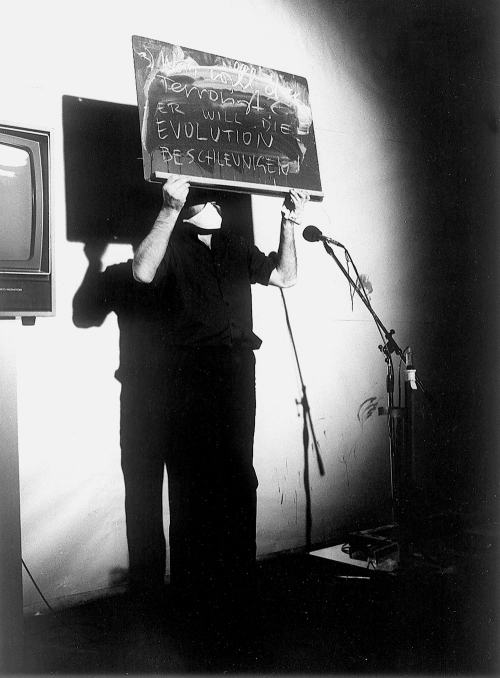

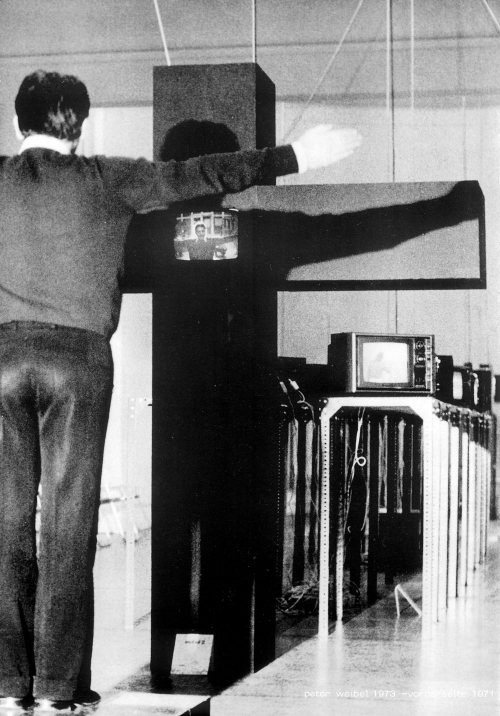

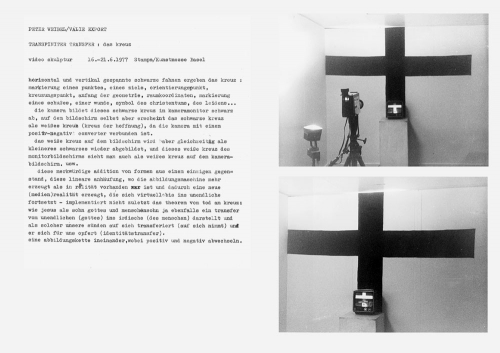

Crucifixion of

Identity

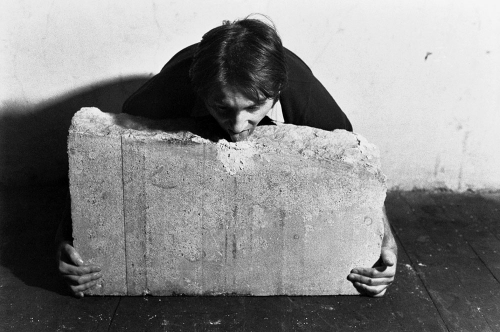

Modern technology has evolved into something radically different from the Greek technē: machine-powered mass production, which has replaced the work of the Greek craftsman, does not simply bring the new forth but, in Heidegger’s words, challenges it forth, turning everything around it into standing reserve. Paradoxically, humans see themselves as the royalty of the world ruling over nature, while in fact technology has turned them too into human resources.

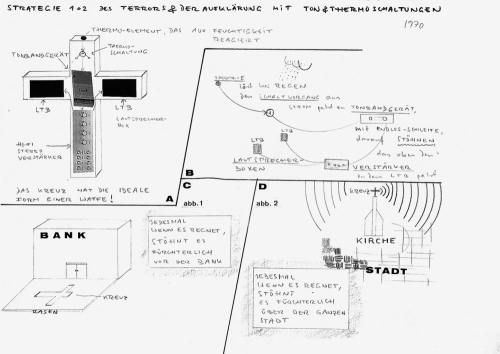

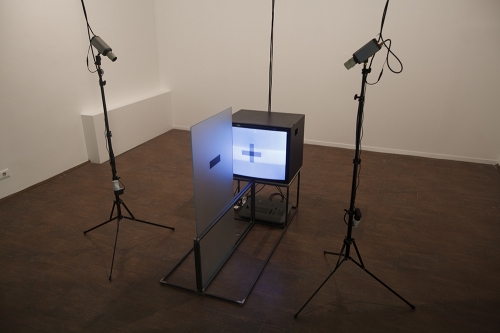

Media reveal the paradoxes and contradictions of the post-industrial society where humans objectify themselves and watch themselves from the outside, lost before the disembodied and all-seeing eye of the camera. In Peter Weibel’s interactive installations technology, which seemed a curious riddle a moment ago, turns into a cold algorithm returning to the spectator his or her alienated image in a distorted time and space. The cross featured in several of Peter Weibel’s works symbolizes the ‘transfer of identity’: from god to a human and humanity in general in the Christian tradition, and from human to his or her image in the case of media representation. As Peter Weibel explains, ‘the cross is the price humankind pays (...) to visually recognize oneself in an image’.

Crucifixion of

Identity

Chants of

the Multiverse

Unlike any other technology, media do not just bring forth that which is not, but also, according to their original and primary function, bring to the human that which was, that which is somewhere else, and (especially with the invention of montage and later with digital technology) that which could be. Transferred to a screen, reality becomes a question, a possibility. If we envisage media as what Marshall McLuhan called ‘an extension of ourselves’ — essentially a new sense organ — then it must give rise to a new sensibility and a new kind of poetry.

To Peter Weibel, media are not only teletechnology (from the Greek tēle, far), making appear before us what is absent here and now, but they are also theotechnology (from the Greek θεός, god), allowing us to extend our universe and create new ones, overcoming the constraints of physical reality like artists overcome the constraints imposed by society, dominant culture and institutions.

Chants of

the Multiverse